A new religion after one rawther

A religious sect founded by a Muslim and whose followers wear saffron speaks of love as the true path to salvation

As the cab turns from the highway after an hour’s journey from Tiruchi, the road narrows abruptly. ‘Meivazhi Salai’ says a small blue board.

Trundling along on the barely there strip of tar, past what would have once been a dense forest but is now a dried up brushwood thicket, we might as well be travelling back into a society left behind by time. The noon prayers are due to start when we finally arrive at a compound in the clearing. “Mouna mani adika pogirom,” (we are going to sound the bell for silence) intones an elderly gentleman at the Sathyadeva Brahma Kulathinar Aalayam (temple). A gentle breeze is stirred up by the trees and a companionable quietude descends on the community.

The novelty of the setting starts to sink in when you spot a signboard barring singles from entering a particular street; the thatched homes whose walls are no more than 4-5 feet high; pots of water and piles of firewood — the rough and tumble of the world outside seems a distant memory already. The settlement houses the followers of Brahma Prakasa Meivazhi Salai Andavargal, who founded a syncretic religion called ‘Marali Kaitheenda Salai Andavargal Meimatham’ in the early 20th century. Meivazhi Salai (True Path) ashram is located in Pudukottai district’s Iluppur taluk.

A syncretic spirituality

Though the sect’s founder was born a Muslim, the tenets of Meivazhi Salai are drawn from all the leading religions of the world. Four volumes of scriptures called ‘Grantham’ preach the oneness of divinity as the essence of worship. The faith’s followers can be from any community, so long as they are believers in God.

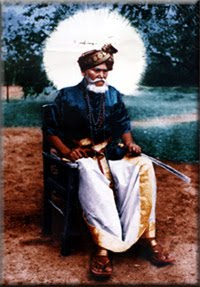

Men who have received the highest form of spiritual teaching (upadesam) directly from the sect’s founder are called ‘Anandars’ and wear saffron shirts, a saffron turban with a crescent pin (called ‘Kilanaamam’), and five-yard waistcloths draped in the ‘panchakacham’ style.

Male followers who haven’t received the upadesam wear white turbans and clothes in colours other than saffron. Women who have received upadesamwear saris and cover their head with a saffron scarf, while other women cover their head with the end of the saris. It is said that 5,049 people embraced the sect’s tenets during the leader’s lifetime, and of these, around a thousand survive.

“Meivazhi Salai satisfied my urge to understand why we worship. The words of Our Lord convinced me that this is the best place to know more about myself,” says Meivazhi Somasundara Anandar, who meets us after prayers at his ‘viduthi’ (as the homes are referred to inside the compound).

No electricity

Somasundara Anandar’s viduthi is a small dwelling of unbaked clay blocks on land owned by the sect. Reed mats are spread out on the floor for seating visitors. The ashram abjures electricity, which explains why we are provided with palm frond fans to deal with the day’s heat. As for the no-entry sign for singles, well, marriage is compulsory for aspiring Meivazhi Salai followers.

“Our Leader used to say that man was made for woman and woman for Man, so would God have rejected marriage?” explains Meivazhi Gunasekara Mudaliar, who is Mr. Somasundara’s son-in-law.

“Marriage helps maintain the naturalness of social relationships and shows that spirituality is not an impediment to a married life,” he adds. Not only does the sect eschew monasticism, it also encourages its followers to be engaged in the world through professional careers and education. Followers address each other as anna (elder brother) and akka (elder sister) regardless of differences in age. Consumption of alcohol, tobacco and non-vegetarian food is taboo.

The founder

Khadar Badsha Rowther was born on the last day of the Tamil month of Margazhi in the mid-19th century to Jamal Hussain Rowther and his wife Peria Thai in Markampatti village, near Karur. He would eventually be better known as Brahma Prakasa Meivazhi Salai Andavargal.

The first Meivazhi Sabha started with 200 followers at Rajagambiram in Sivagangai district. The second one was established in Tirupattur, in 1933. By 1939, the swelling numbers of followers led the Sabha to Madurai, where a sprawling commune was founded on Arupukottai Road.

But in 1942, the land was acquired by the British during World War II for a sum of ₹1,37,750. That same year, the commune was re-established in Papanachivayal, in Pudukottai district, on a 100-acre complex. Meivazhi Salai has been functioning from here since November 5, 1942.

Andavargal passed away (the followers refer to his death as ‘Maha Samadhi’) on February 2, 1976, and was buried in his usual place of ‘tapas’ in the ‘Ponnaranga Devalayam’ of the ashram.

The sect faced a credibility crisis in March 1976, when Customs and Excise Department officers raided the hermitage in a weeklong operation that unearthed gold and silver ornaments from the Pudukottai campus. “The items were buried because there were no cupboards or other storage facilities in the Pudukottai ashram,” says Mr. Mudaliar. “The government sued us for illegal hoarding of wealth, but eventually it lost the case.”

Mr. Mudaliar was an exception to the Meivazhi Salai rule when he was initiated into the sect at the age of 17. “I joined the faith in 1973, and feel blessed to have seen the Lord,” says the 65-year-old, who retired as deputy general manager at BHEL.

“My father was a personnel manager in the Railways, and more used to European culture. He said that I was a grown-up who could decide for myself. My parents came to see Our Master but they did not join the faith,” he adds.

Against idol worship

The ashram’s main shrine is an open structure on sandy ground, covered only by a thatch that is replaced every five years. Gas stoves are forbidden because of the fire hazard that the extensive thatching poses.

The curtains on the shrine, when parted, show an empty platform. “Our Lord has forbidden us to keep photos of him. In 1973, he recalled all the photos that he had given to followers and burned them because he felt it would encourage idol worship,” explains Mr. Mudaliar. There have been some concessions to modernity of late: solar power panels have allowed for small pedestal fans in the viduthis, and a complex of public toilets has been added.

There is a gentle fragrance of fresh flowers and sandalwood oil wafting inside the Thiru Maaligai, the two-roomed home where Salai Andavargal lived with his family. A stone- and rivet-studded wooden chest is opened to show the Grantham, behind a gauzy curtain on the bed used by the sect’s founder.

As the day’s visit comes to a close and the cab prepares to rejoin the traffic of the highway, the absence of gates in the ashram compound seems to echo the Meivazhi Salai philosophy in its own subtle way.

more info : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meivazhi

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment